Unveiling the Veil of Shadows

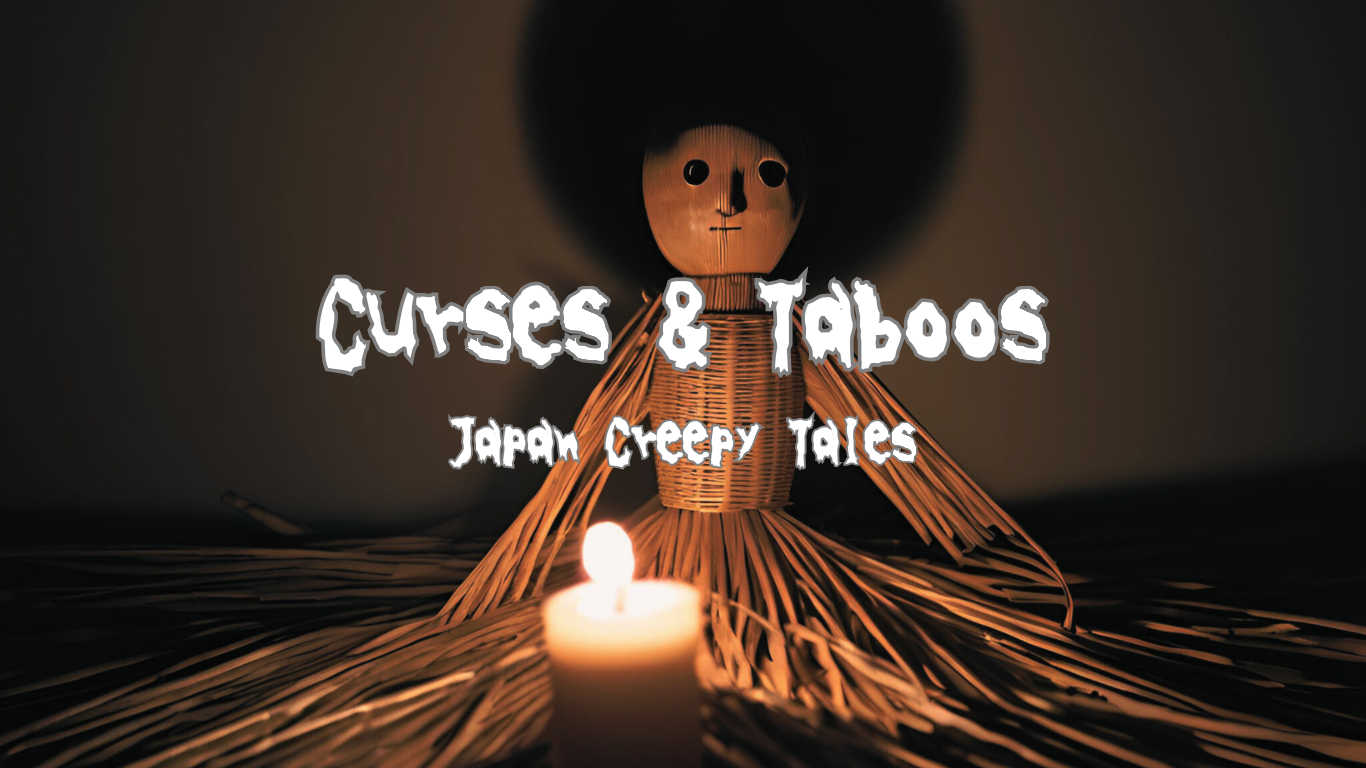

Greetings, seekers of the eerie and the unexplained. GhostWriter here, ready to pull back another layer of Japan’s shrouded folklore, where ancient fears coil around everyday objects and customs. Tonight, we delve into a particularly chilling nexus of belief: the profound reverence and terror associated with serpents, and a seemingly innocuous yet deeply unsettling taboo surrounding one of Japan’s most iconic garments – the kimono.

In the vast tapestry of Japanese mythology and superstition, the serpent, or “hebi,” occupies a dualistic role. It is revered as a messenger of the gods, a guardian of water, and a symbol of wisdom and renewal, often associated with powerful deities like Ryujin, the dragon god of the sea. Yet, beneath this veneer of divine benevolence, there lies a darker, more ancient fear. Tales abound of vengeful serpents, shapeshifting entities, and potent curses delivered by these slithering creatures, often targeting those who have desecrated sacred places, broken vows, or simply earned their ire through inexplicable circumstances. Their scales, often discarded, are whispered to hold remnants of their power, both sacred and profane, capable of bestowing blessings or, more often in the darker narratives, inflicting lingering torment.

Simultaneously, the kimono, a garment of exquisite beauty and profound cultural significance, is far more than mere clothing. It is an embodiment of tradition, status, and the very spirit of Japan. From vibrant celebrations to solemn ceremonies, the kimono marks life’s passages. However, nestled within its meticulously folded layers lies a potent taboo, a whisper of dread that has permeated generations: the act of wearing a kimono inside out. This seemingly simple mistake is not just a breach of etiquette; it is, in some chilling accounts, an invitation to a realm beyond the living, a silent cry that is said to resonate with ancient, malevolent forces.

Tonight’s chilling exploration centers on the intersection of these two potent elements: the “Curse of the Serpent Scales” and the “Wearing Kimono Inside Out Taboo.” While seemingly disparate, some whispers from the dark corners of forgotten villages and dusty archives suggest a terrifying connection. It is said that a casual disregard for the kimono’s sacred order, particularly when one’s spirit is vulnerable or troubled, can inadvertently attract the attention of ancient serpentine entities, whose curses manifest in ways that are both subtle and horrifying. The inside-out kimono, in these dreadful tales, becomes a macabre uniform, a signifier not merely of death, but of a soul ensnared by something primal and cold-blooded.

Prepare yourselves, for as we unfold these tales, you may find that some of the deepest horrors lie not in mythical beasts themselves, but in the unwitting acts of humans that draw their ancient wrath. The question remains: is this merely an old wives’ tale, or does the very fabric of tradition hold threads of a terror that can still coil around the unwary? Let us proceed into the shadows, where the rustle of silk might just be the slithering of scales, and a misplaced fold can unravel a life.

Unveiling the Coiled Horror

The Kimono’s Silent Scream: A Garment of Life and Death

The kimono, an icon of Japan, is a garment imbued with centuries of cultural significance, its very folds and patterns speaking volumes about the wearer’s occasion, status, and even inner world. From the vibrant hues of a festival kimono to the subdued elegance of daily wear, it is a testament to Japanese aesthetics and a profound connection to tradition. Yet, beneath its outward beauty lies a silent language of solemnity, particularly concerning the rites of passage from life to death. Understanding this silent language is crucial to grasping the terror of the “inside-out” taboo.

For the living, the kimono is always worn with the right side of the garment tucked under the left (migi-mae). This is not merely a stylistic choice; it is a fundamental aspect of Japanese attire, ingrained from childhood, a subtle yet omnipresent detail that signifies life, order, and the mundane world. It is an unspoken rule, followed almost instinctively, a part of the cultural DNA. To deviate from this is to commit a grave faux pas, an immediate visual cue that something is amiss, a signal that might subtly disturb the sensibilities of those around you, even if they cannot articulate precisely why.

However, when a person departs from this world, the kimono takes on a vastly different symbolism. It becomes a shroud, a final attire for the journey into the unknown. For the deceased, the kimono is traditionally dressed left side over right (hidari-mae) – the complete reverse of how it is worn by the living. This inversion is a deliberate and profound symbolic act, signifying the transition to the world of the dead, a realm where earthly rules no longer apply. It is a visual boundary, separating the living from those who have passed beyond the veil. This custom is so deeply ingrained that to see a living person dressed left-over-right can send a shiver down the spine, evoking immediate thoughts of death, illness, or an ill omen. It is a stark reminder of mortality, an uncomfortable glimpse of the other side.

But there is another, even more chilling practice associated with dressing the dead: sometimes, the kimono is not only worn left-over-right but is also deliberately turned inside out. This practice, though less universally observed than the left-over-right custom, carries a particularly potent layer of symbolic horror. The act of turning a garment inside out for the deceased is said to signify a complete reversal of the mundane world, a rejection of earthly life and its customs. It implies a total severing of ties, a surrender to the underworld, or perhaps, a desperate attempt to ward off lingering spirits by presenting oneself in a distorted, unrecognizable form. It is a visual representation of absolute disengagement from the human realm, an embrace of the ethereal and the unknown.

The profound unease and primal fear associated with seeing a living person wear a kimono inside out, therefore, stems from this deep-seated cultural understanding. It is not just about a fashion faux pas; it is a visual scream, a silent declaration that the wearer has either inadvertently crossed into the realm of the dead, or worse, has been marked by forces that belong solely to that spectral domain. Such a sight might whisper of a soul teetering on the precipice of departure, or perhaps, a soul already claimed by something unholy. The garment, designed for beauty and comfort, transforms into a macabre uniform, hinting at a presence that is profoundly out of place, an unsettling disruption of the natural order. It serves as a chilling reminder that some boundaries, once crossed, cannot be uncrossed, and that a simple piece of clothing can carry the weight of life, death, and something far more terrifying.

The Serpent’s Ancient Pact: Folklore and Fear

Japan’s relationship with serpents is deeply complex, woven into the very fabric of its spiritual and mythological landscape. Unlike Western perceptions where snakes are often symbols of temptation or evil, in Japan, the serpent, particularly in its more exalted form as the dragon (ryu), holds a revered status. They are venerated as deities of water, bringing rain for bountiful harvests, guarding sacred places, and bestowing wealth and good fortune. Shrines dedicated to serpent kami (spirits or deities) dot the landscape, offering solace and protection.

However, this reverence is often intertwined with an ancient, primal fear. The same creature capable of bestowing blessings is also capable of unleashing terrifying wrath. Stories of monstrous serpents like Yamata no Orochi, the eight-headed, eight-tailed beast slain by Susanoo, abound in ancient chronicles, illustrating their destructive power. Local legends, whispered in hushed tones, tell of vengeful serpents guarding hidden treasures, exacting retribution for perceived slights, or even shapeshifting into human form to lure the unwary. These tales often serve as cautionary warnings, emphasizing respect for nature, sacred spaces, and the delicate balance between the human and spiritual worlds. The power of the serpent, therefore, is double-edged: capable of creation and destruction, blessing and curse.

Central to the fear of serpent curses is the potent symbolism of the “scale.” The serpent’s scales, shimmering and protective, symbolize regeneration and immortality through the shedding of skin. Yet, in the context of curses, scales take on a far more sinister meaning. They become a visible manifestation of transformation, disease, or a reptilian pact. To see scales appearing on one’s skin in folklore is often a horrifying sign of a creeping malady, an unholy metamorphosis, or the indelible mark of a powerful curse. It suggests a loss of human form, a descent into something cold-blooded and inhuman, a slow but inevitable assimilation into the cursed entity’s nature. This visible sign of transformation is particularly terrifying because it is an internal change, becoming horrifyingly external. A person afflicted by a serpent’s curse might find their skin inexplicably dry and scaly, their eyes developing an unnerving gleam, or their very being growing cold to the touch, echoing the cold-blooded nature of their tormentor. These physical manifestations serve as a constant, horrifying reminder of the curse, stripping away one’s humanity piece by piece.

Serpent curses, unlike some other forms of spiritual affliction in Japanese folklore, are often depicted as particularly tenacious and difficult to break. They can be hereditary, passing down through generations, or cling to specific places, making certain locales forever tainted by their ancient malice. They manifest in myriad ways: inexplicable misfortunes, debilitating illnesses that doctors cannot diagnose, strange accidents, or even a profound, creeping sense of dread that permeates every aspect of a victim’s life. The fear stems not just from the suffering, but from the feeling of being hunted by something ancient and relentless, a primal force that cannot be reasoned with or escaped. The very thought of encountering such a curse, let alone becoming its victim, sends shivers down the spines of those who understand the depths of Japanese folklore. It is a terror that lingers, a subtle chill in the air, a whisper of scales against stone in the dead of night.

The Twisted Thread: Linking Kimono and Serpent’s Curse

Now, let us weave together the two chilling threads of our narrative: the taboo of the inside-out kimono and the ancient malevolence of the serpent’s curse. While historical records may not explicitly detail a direct link, the confluence of these deep-seated fears in Japanese folklore has given rise to unsettling whispers and dark tales, suggesting a macabre connection where one might inadvertently invite the other. It is in these shadows that the true horror of our subject resides.

One might hear tales, particularly from older generations in secluded mountain villages, of “The Weaver’s Omen.” It is said that in an era long past, a renowned silk weaver, consumed by grief after the sudden loss of her beloved child, became deeply distraught. In her sorrow and confusion, she inadvertently donned her finest kimono inside out, mistaking the reversed pattern for the dullness of her own despair. Over the following days, a strange, creeping ailment began to manifest upon her skin. Shimmering, iridescent patterns, eerily reminiscent of serpent scales, started to appear on her arms and neck, spreading slowly despite all efforts to conceal them. Her touch grew cold, and her eyes, once filled with human warmth, seemed to hold a reptilian glint in the fading light. As the curse deepened, her family, out of a misguided sense of sympathy or perhaps a growing, unsettling compulsion, also began to wear their kimonos inside out, their grief transforming into a collective, horrifying affliction. The village, witnessing this unsettling progression, whispered of a serpent deity, angered by the family’s despair, which had found an opening through the desecrated garment, turning their inner turmoil into an outward, scaly manifestation of despair and curse.

Another chilling legend speaks of “The Serpent Priestess’s Retribution.” Long ago, near a shrine nestled deep within a mist-shrouded forest, there lived a revered priestess who served a powerful, yet volatile, serpent deity. When she was tragically betrayed by a local lord, her immense sorrow and rage were said to have invoked the deity’s ancient wrath. Those who had wronged her, or even those merely associated with the lord, began to suffer an inexplicable urge. They would awaken in the dead of night, compelled to turn their kimonos inside out before attempting to return to their restless sleep. As days turned into weeks, their bodies would grow unnaturally cold, their voices becoming raspy whispers, and their skin would begin to show faint, scale-like markings beneath their clothing. It was said that the inside-out kimono became the chosen uniform for the cursed, a visible sign that their souls had been twisted and inverted by the serpent’s ancient vengeance. The garment, meant to cover and protect, instead became a porous membrane, allowing the malevolent spirit of the serpent to seep into their very essence, transforming them from within.

The core of this terrifying connection lies in the notion that the kimono, when worn inside out, acts as a potent conduit, an open invitation to forces from the spirit realm. By reversing its natural order, one is not merely defying human custom; one is potentially mirroring the inverted nature of the supernatural world, a realm where order is chaos and life is death. The most chilling aspect of this particular fusion of fears is the belief that the inside-out kimono does not just signify impending death or a visit from a ghost; it becomes a visual manifestation of an internal, reptilian transformation or possession. It is as if the curse, once it takes hold, begins to subtly invert the wearer’s very being, starting with their outward appearance and slowly creeping inwards, until their humanity is peeled away like shedding skin. To encounter someone dressed in such a manner, particularly in an unexpected place or at an unusual hour, is said to send a shiver to the soul, for it implies that the boundaries between worlds have blurred, and a serpent’s ancient wrath might just have claimed another unsuspecting victim, leaving them marked, both inside and out, by the chilling touch of scales.

Whispers from the Beyond: Accounts of the Accursed

The chilling narratives surrounding the “Curse of the Serpent Scales” and the “Kimono Inside-Out Taboo” are not merely static tales from forgotten scrolls. They are kept alive through generations of whispered accounts, unsettling rumors, and eerie sightings that persist even in modern times, reminding us that ancient fears still coil subtly in the subconscious of Japan. These are not definitive facts, but rather the disquieting echoes of a deeply rooted dread, tales passed from one trembling lip to another.

It is said that in certain remote villages, nestled deep within mist-shrouded valleys or perched on windswept coastal cliffs, during long, moonless nights, one might catch a glimpse of a solitary figure wandering through the narrow pathways. Their silhouette is unmistakably human, yet a profound sense of wrongness emanates from them. As they draw closer, or if one’s gaze is drawn to them by an inexplicable compulsion, the truth becomes horrifyingly clear: their kimono is visibly inside out. To meet their gaze is to feel a chill that penetrates to the very bone, for their eyes are said to flicker with an unnatural, reptilian gleam, a cold, unblinking intensity that speaks of ancient, non-human wisdom, or perhaps, utter, lifeless despair. Some whispers suggest that these are not spirits in the conventional sense, but rather individuals who have been claimed by the serpent’s curse, still bound to the human realm but fundamentally transformed, their human essence slowly being shed like a serpent’s skin.

More unsettling still are the stories of sudden, inexplicable illnesses or misfortune that have befallen those who, perhaps in a moment of extreme emotional distress or profound ignorance, have dared to don a kimono inside out. There are hushed accounts of individuals who, after such an act, began to experience a persistent, unyielding coldness that no amount of warmth could dispel. This coldness, it is said, would emanate from within, making them feel as if their very blood had turned to ice. Others reportedly developed strange, shimmering patterns on their skin, subtle at first, perhaps mistaken for a rash or a skin condition, but gradually evolving into distinct, iridescent markings that bore an uncanny resemblance to scales. These patterns, often accompanied by a raw, itching sensation or an unnatural dryness, are said to be the serpent’s mark, a visible sign of its insidious influence taking root.

The curse, it is whispered, often manifests not only physically but also psychologically. Victims are said to develop an aversion to sunlight, preferring the cool, damp shadows. Their voices might grow hoarse or whispery, their movements becoming strangely fluid, almost serpentine. Perhaps most tormenting are the dreams: vivid, recurring nightmares filled with serpentine coils, vast, unblinking reptilian eyes, and a chorus of whispers that seem to promise an eternity of cold, silent transformation. These dreams are said to be so potent that they begin to blur the lines between sleep and waking, leaving the afflicted in a constant state of dread and disorientation.

The ultimate dread, of course, is the gradual loss of one’s humanity. It is believed that as the curse progresses, the victim slowly becomes more like the cursed entity itself, shedding not just their skin, but their very identity, their memories fading, their emotions chilling, until they are but a vessel for the serpent’s will or a lingering echo of its ancient sorrow. There are no definitive rituals to break this particular curse, for its origins are often too ancient and its hold too strong. However, local lore occasionally offers fragments of advice for avoidance: an unwavering respect for traditional customs, never wearing a kimono inside out under any circumstances, even in play or jest; avoiding certain ancient pathways or neglected shrines rumored to be associated with serpent deities; and perhaps, always carrying a small, polished stone, said to ward off unwelcome spiritual attention. But even these precautions, it is whispered, may not be enough if a powerful serpent deity has already set its cold gaze upon you. For once the scales begin to show, and the kimono is worn awry, the journey into the reptilian darkness may be irreversible.

Beyond the Fabric: Cultural Echoes and Psychological Impact

The enduring power of such taboos and curses in Japanese society, particularly those intertwined with profound cultural symbols like the kimono and ancient entities like serpents, goes far beyond mere superstition. It delves into the collective unconscious, reflecting deeply ingrained anxieties and the fundamental human need to understand and maintain order in a world often perceived as chaotic and unpredictable. The “Curse of the Serpent Scales” and the “Kimono Inside-Out Taboo” are not just scary stories; they are cultural echoes, cautionary tales that reinforce societal norms and respect for the delicate boundaries between life and death, the human and the supernatural.

The psychological fear evoked by these narratives is particularly potent because it taps into several core human anxieties. Firstly, there is the fear of the unknown and the unseen. The idea that a simple, unintentional act – like incorrectly wearing a garment – can open a portal to ancient, malevolent forces is deeply unsettling. It suggests that danger can lurk in the mundane, that one can stumble into horror without even realizing it. Secondly, there is the profound fear of internal transformation and the loss of self. The idea of one’s body slowly morphing, acquiring reptilian characteristics, or having one’s consciousness subtly altered by an ancient curse is a terrifying prospect. It speaks to the fear of losing control over one’s own identity and becoming something alien and abhorrent, a shell of one’s former self. This psychological terror is often far more pervasive and debilitating than any physical harm, as it corrodes the very essence of what it means to be human.

Furthermore, these stories serve as powerful social mechanisms. They reinforce respect for tradition, for the meticulous details of cultural practices that, on the surface, might seem arbitrary. The strict adherence to how a kimono is worn, the specific fold, the orientation of the layers – these are not just aesthetic preferences. They are cultural signifiers, imbued with generations of meaning, and stories like the serpent’s curse serve to underscore their importance. By associating a severe supernatural consequence with a breach of this custom, the taboo functions as a strong deterrent, ensuring the preservation of cultural practices and a continued reverence for the unseen forces that are believed to govern the world. It is a subtle form of social control, a reminder that disrespecting established norms can have dire, even supernatural, repercussions.

Even in contemporary Japan, where scientific understanding and modern rationalism prevail, the underlying unease associated with these taboos persists. While fewer people might explicitly believe in a literal serpent’s curse, the sight of a kimono worn inside out still evokes a visceral sense of dread, a lingering whisper of something deeply wrong or ill-fated. It is a testament to the enduring power of folklore, how ancient fears can continue to subtly influence perceptions and stir discomfort, even when explicit belief has waned. The stories continue to be told, perhaps with a touch of irony or a knowing smile, but always with that underlying shiver of caution. The kimono, a symbol of beauty, grace, and tradition, ironically becomes a conduit for primal fear when its order is disturbed, revealing the thin veil between the comforting familiarity of daily life and the chilling, ever-present possibility of ancient, coiled horrors.

The Ever-Coiled Shadow

We have ventured deep into the shadowy intersection where ancient serpentine curses coil around one of Japan’s most cherished cultural garments. What began as a mere exploration of two distinct elements of Japanese folklore – the feared “Curse of the Serpent Scales” and the disquieting “Wearing Kimono Inside Out Taboo” – has revealed a chilling potential synergy, whispered in the hushed tones of generations past. It is said that in moments of profound vulnerability, or through an unwitting disregard for sacred custom, a simple act of wearing a kimono in reverse can unfurl an invitation to an ancient, cold-blooded malevolence, drawing the serpent’s wrath and transforming the unwary from within.

The profound horror of these tales lies not just in the grotesque physical manifestations of the curse – the creeping cold, the shimmering scales, the reptilian gleam in the eyes – but in the insidious psychological torment, the slow, chilling erosion of one’s humanity. The inside-out kimono, far from being a simple sartorial mistake, becomes a visible declaration of a soul teetering on the brink, or perhaps, already claimed by something ancient and inhuman. It is a uniform of the afflicted, a stark warning to those who might witness it, serving as a chilling reminder that some boundaries, once crossed, cannot be uncrossed, and some transformations are irreversible.

Japanese folklore is a rich tapestry woven with threads of reverence and fear, light and shadow. It reminds us that sometimes, the deepest horrors lie not in mythical beasts themselves, but in the subtle violations of deeply ingrained cultural norms, especially those concerning life and death, order and chaos. The traditions surrounding the kimono are not mere etiquette; they are, in some profound sense, shields against the unseen, safeguards against the malevolent forces that are always said to linger just beyond our perception, waiting for an opening. To disregard them is to invite a chill that permeates the very soul.

So, the next time you encounter a fragment of Japanese tradition, perhaps a seemingly minor custom or a whispered taboo, consider the centuries of fear and reverence that have shaped it. For in the world of Japan’s creepy tales, even the most mundane objects can become conduits for the profound and the terrifying. And remember, dear readers, until next time, keep your senses sharp, your respect for tradition unwavering, and your kimonos, for your own sake, always, always right-side out.